Farmin Shahabuddin, MPH, Ammu Dinesh, and Claire Viscione, National Center for Health Research

Belly fat is common among men and women. However, when a person’s body shape looks more like an apple than a pear, that could increase their likelihood of developing cancer or other serious diseases.

More than two-thirds of adult Americans are overweight or obese.1 Most people know that obesity increases the risk of diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. But did you know that being overweight also increases your chances of developing cancer, and that having an “apple” body shape due to belly fat can increase your chances of developing cancer and dying from several serious diseases, even if you are not overweight?

Why is belly fat dangerous?

Whether your body fat is located at your waist (giving you an apple shape) or hips (giving you a pear shape) makes a difference to your health. Women tend to gain more belly fat as they get older. Regardless of their weight, white, black, and Latina women with a waistline measurement of 35 inches or more have higher health risks. This is also true for Asian women with a waistline of 31 inches or more. Although it is important to get rid of excess fat in general, belly fat is the most threatening to your health.

Unlike the fat that sits just beneath the skin, the fat that sits around internal organs is called visceral fat.2

This fat is the most dangerous, and it is typically what shows up as belly fat. Measuring your waistline is important since you can get a good idea of whether you have a dangerous amount of belly fat.

You can check your waist circumference at home with a simple tape measure. Wrap the tape around your bare waist, above your hipbones, after gently exhaling. As you can see from the table below, a waist size of 40 inches or more for men and 35 inches or more for women is considered high risk.

Table 1. What does your waistline measurement mean? 2

Table 1. What does your waistline measurement mean? 2

Additionally, the waist-to-hip ratio is also another important indicator to determine whether you are at risk for abdominal obesity. The waist-to-hip ratio can be measured by dividing your waist measurement (in inches/cm) by your hip measurement (in inches/cm). The World Health Organization (WHO) states that abdominal obesity is defined as a waist-hip ratio above 0.90 for males and above 0.85 for females. 3 Use this calculator to measure your ratio. Even if you are not overweight or obese, having a lot of belly fat can more likely lead to developing cancer and other chronic health conditions.

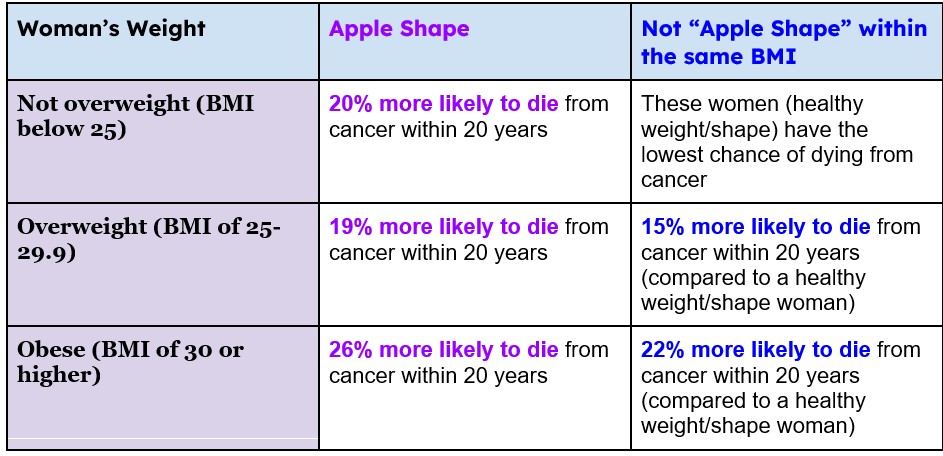

Physicians often use the body mass index (BMI) to estimate whether an individual is overweight or obese. To figure out your BMI, use the chart below, and enter your height and weight into this calculator. The chart shows how being overweight or having an apple shape increases your chances of dying from cancer compared to women who are not overweight and do not have an apple shape.

Table 2. Likelihood of death due to cancer in women based on BMI. 3

Table 2. Likelihood of death due to cancer in women based on BMI. 3

You can see that women who were not overweight or obese but had extra belly fat were almost exactly as likely to die from cancer as overweight women with extra belly fat (20% compared to 19%).

As experts have increasingly criticized reliance on BMI as the way to define overweight and obesity, they worked together to develop a new definition that includes belly fat and related proportional measurements, either in addition to a traditional BMI obesity measure or independent of the BMI obesity measure. In 2025, this definition has already been endorsed by at least 76 professional organizations. 4 It classifies a person as obese if any of the following criteria are met:

- A BMI greater than 40 and at least one elevated proportional measure of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and/or waist-to-height ratio.

- At least two high proportional body measurements, regardless of BMI – for example, a person with both a large waist and a high waist-to-hip ratio could meet the definition.

- Excess body fat is assessed by dual-energy x-ray or similar technology to measure fat mass.

Using this updated definition, researchers found that approximately 69-75% would be classified as obese, compared with 43% under the traditional BMI definition. 4,5 This large difference was due to the addition of adults who had excess belly fat but a normal BMI. For example, one study found that 39% of adults with a normal BMI and 80% of adults who were overweight had obesity based on excess belly fat or unhealthy body proportions, showing that BMI alone often overlooks people with unhealthy belly fat.5

Furthermore, people newly identified as obese under the updated definition had higher rates of serious health problems. For example, 12% had diabetes compared with about 2% of adults who had a normal BMI and a healthy waistline. Likewise, about 10% had a heart attack or stroke, compared with about 2% in the healthier-fat-distribution group. In terms of mortality, about 8% died during the study period, compared with about 3% of adults with a normal BMI and normal fat distribution. 4 These findings show that the new definition does not simply change how obesity is counted—it does a better job of identifying adults with excess belly fat who are more likely to develop serious medical problems.

Researchers emphasized that future research and medical care should consider BMI and measures of body fat distribution to more accurately identify patients who would benefit from treatment to prevent weight-related diseases. Since that new definition has not yet been used in most studies, this article focuses on studies evaluating the health impact of body fat with or without a high BMI.

Research on Belly Fat and Cancer

Several studies have looked at the relationship between belly fat and cancer and other serious diseases. One study in 2013 followed more than 3,000 men and women for 7 years. They used CT scans and physical exams to look at the fat throughout the body. Over the course of the study, the men and women developed 141 cases of cancer, 90 heart-related incidents, and 71 deaths from various causes. The study found that people with more belly fat, specifically visceral fat, were about 44% more likely to develop cancer and heart disease, even when adjusting for waist circumference. 6

Another study in 2019 followed over 150,000 post-menopausal women ages 50-79 for about 20 years.7 This study found that women who have extra belly fat are at a higher risk of death regardless of their weight. Causes of death in the study included cardiovascular disease and cancer. The women of normal weight who had extra belly fat tended to be older, nonwhite, and with less education and income. They were also less likely to use menopausal hormones and to exercise.

Recent studies provide more detailed evidence about how belly fat raises cancer risk and affects cancer after diagnosis. A 2022 study that followed 94,000 adults for more than ten years found that people were about 30% more likely to develop colorectal cancer. The researchers found that belly fat increases inflammation and makes it harder for cells to use insulin properly, which are the two changes that make it easier for cancer to grow. 8

A 2021 study looked at people who were already being treated for stage III colorectal cancer. Those with higher amounts of belly fat had lower survival rates – about 79% were still alive three years after treatment, compared with 88% of people with less belly fat. People who had more belly fat were also three times as likely to have their cancer spread inside the abdomen. 9 This shows that belly fat can affect not just who gets cancer but how well patients respond to treatment and recover.

Colorectal cancer may not be the only type of cancer affected. New evidence suggests that fat may contribute to the growth of various types of cancer cells. A 2022 scientific review found that cancers can use fatty acids as a source of energy, so that excess fat in the body may act as “fuel” for tumor growth. 10 Other studies show that obesity can disrupt the body’s gut microbiome, changing the balance of healthy and harmful bacteria. A 2023 review concluded that these changes in bacteria can increase toxins, inflammation, and immune dysfunction, all of which can promote gastrointestinal cancers. 11

Belly fat also increases the chances of prostate cancer. Researchers report that men with more belly fat are more likely to develop prostate cancer, and that is true even for men with a normal BMI. 12 A 2018 scientific review of the association between abdominal obesity and prostate cancer reports that larger waist size and central fat are associated with higher prostate cancer risk, particularly for more aggressive and advanced stages of cancer. 13

Belly Fat and Heart Disease and Related Health Problems

For both men and women, extra belly fat raises the chances of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes – the leading causes of death in the United States. 14 Visceral fat releases substances that trigger chronic inflammation and damage blood-vessel walls, making arteries stiffer and more likely to clog. Over time, this increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, and metabolic disease, even in people whose BMI is normal.

A major international study published in JAMA Network Open in 2025 found that many people who appear to have a healthy weight still have unhealthy amounts of belly fat. 15 Researchers analyzed data from more than 470,000 adults in 91 countries and discovered that about one in five adults worldwide (21.7%) had a normal BMI but excess belly fat, also called abdominal obesity. People with a normal BMI and excess belly fat had higher levels of all four major cardiometabolic risk factors measured in the study. It may seem surprising that 30% had high blood pressure, 17% had diabetes, 28% had high cholesterol, and 23% had high triglycerides. These conditions are among the leading causes of heart disease and stroke.

In fact, adults with abdominal obesity had 30% with high blood pressure, compared with about 20% of adults with both a normal BMI and a healthy waistline. About 17% had diabetes, compared with about 9% in the healthy-waistline group. About 28% had high cholesterol, compared with about 19% in the healthier-fat-distribution group. About 23% had high triglycerides, compared with about 13% of adults with a normal BMI and a healthy waistline. The study also found that people who had belly fat were less likely to be physically active and ate fewer fruits and vegetables. The researchers concluded that waist size should be treated as an important health indicator because it identifies people who may seem healthy by BMI standards but are more likely to develop serious health problems such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

A recent imaging study in 2025 from Germany examined how belly fat affects the heart in 2173 adults ages 45 to 74. 16 The researchers used detailed MRI scans to compare heart structure in people with obesity based on waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) and those with obesity based on BMI. They found that about 80 out of 100 adults had obesity according to WHR, while about 20 out of 100 had obesity based on BMI alone. Adults with more belly fat had larger, thicker heart muscle and smaller heart chambers, which means the heart pumps less blood with each beat.

Even a small increase in WHR was linked to noticeable changes in heart structure, including a heavier left ventricle and smaller chamber sizes on both the left and right sides of the heart. These changes, known as cardiac remodeling, may be early signs of strain on the heart. The heart changes were greater in men than in women. In men, belly fat was more closely linked to the shrinking of the heart’s right ventricle, which pumps blood to the lungs. Women showed the same pattern but to a lesser degree. The researchers concluded that belly fat may be more important than BMI for identifying adults who are already developing harmful changes in heart structure, and that clinicians should pay closer attention to the waist-to-hip ratio when evaluating heart health.

What can you do?

As you can see, belly fat can be very dangerous, especially for women, even if they are not overweight. Losing weight or preventing weight gain can lower health risks. By exercising regularly, you can get rid of unhealthy belly fat. It is also important to change your diet to eat foods that are high in nutrients and essential vitamins. You can do this by eating more fresh vegetables, nuts, and whole-grain breads instead of processed meat, red meat, candy, pasta, and white bread. These few changes can help you lose belly fat and improve the quality and length of your life.

Local bans on unhealthy food and drinks may also be effective in reducing belly fat. A 2019 study shows that a ban on the sale of sugar-sweetened beverages at a large college campus substantially decreased consumption and led to significantly less belly fat.17 Students who stopped drinking the beverages had improved insulin resistance and lower cholesterol. The combination of the ban and a brief motivational talk was even more effective than the ban by itself.

Latest Evidence on What Works and What Doesn’t

The public often sees ads promising to “melt belly fat fast”. Recent studies show which methods help reduce belly fat and which do not.

What Works

- Regular Exercise: Aerobic activity, such as brisk walking, swimming, or cycling, is one of the most effective ways to reduce visceral fat. A 2023 study found a clear “dose-response” effect: more aerobic exercise produced greater belly-fat reduction.18

- Strength Training: Adding resistance exercise two or more times per week helps preserve lean muscle while reducing overall body fat. 19

- Healthy, Sustainable Eating: Johns Hopkins Medicine recommends limiting refined carbohydrates and added sugars, while emphasizing vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. In other words, a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and olive oil helped people lose visceral fat while maintaining muscle mass. 20

- High-Intensity Workouts: In younger adults with overweight or obesity, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and aerobic exercise both significantly reduced visceral fat. 21

- Healthy Habits Beyond Exercise: Harvard experts note that enough sleep, avoiding smoking, and managing stress all help prevent fat from collecting around the waist. 22

What Doesn’t Work

- Spot-Reduction Exercises: Doing only sit-ups or crunches won’t specifically burn belly fat. 23

- Alternate-Day Fasting Alone: A 2021 study found that belly fat was resistant to every-other-day fasting if it is not combined with other lifestyle changes. 23

- “Fat Burning” Pills, Creams, or Belts – None of these products has been proven to reduce visceral fat safely or effectively. 24

What This Means for You:

- Cancer risk: Belly fat increases the chances of developing colorectal, breast, and other cancers – even in people who are not overweight.

- Cancer outcomes: People with more visceral fat may not live as long as others after a cancer diagnosis. Additionally, people with more visceral fat often have lower survival rates after cancer treatment.

- Heart Disease and Related Serious Illness: Extra belly fat raises inflammation and insulin resistance, which can lead to heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes for both men and women.

- Prevention works: The most effective ways to reduce belly fat are regular aerobic and strength exercise, a healthy diet, and consistent lifestyle habits.

- Don’t be fooled: Restrictive fasting, supplements, and “spot reduction” exercises do not work.

The Bottom Line

Belly fat is more than a cosmetic concern — it is a health risk. Reducing belly fat through regular physical activity, healthy eating, and other health habits reduces your chances of developing cancer or other serious diseases. No shortcut, pill, or single exercise will work.

Learn more about how extra body fat can increase your risk for developing cancer, and how you can make a commitment to your health and reduce risky belly fat:

- Weight and Cancer: What you need to know

- Eating Habits That Improve Health and Help with Weight Loss and BMI

- Obesity in America: Are you part of the problem?

All articles on our website have been approved by Dr. Diana Zuckerman and other senior staff.

References:

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats- Overweight Prevalence. CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm. Updated June 13, 2016.

- Ma, W. Y., Yang, C. Y., Shih, S. R., Hsieh, H. J., Hung, C. S., Chiu, F. C., Lin, M. S., Liu, P. H., Hua, C. H., Hsein, Y. C., Chuang, L. M., Lin, J. W., Wei, J. N., & Li, H. Y. (2013). Measurement of Waist Circumference: midabdominal or iliac crest?. Diabetes care, 36(6), 1660–1666. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-145

- Ashwell, M., & Gibson, S. (2016). Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: Simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’ based on BMI and waist circumference. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010159. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010159

- Fourman LT, Awwad A, Gutiérrez-Sacristán A, et al. Implications of a New Obesity Definition Among the All of Us Cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2537619. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.37619

- Al-Roub NM, Malik D, Essa M, et al. Body Mass Index and Anthropometric Criteria to Assess Obesity. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(12):e2549124. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.49124

- Britton KA, Massaro JM, Murabito JM, Kreger BE, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Body Fat Distribution, Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and All-Cause Mortality. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013; 62(10): 921-925. http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/62/10/921.

- Sun Y, Liu B, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Caan BJ, Rohan TE, et al. Association of Normal-Weight Central Obesity With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Postmenopausal Women. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197337. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31339542.

- Li W et al. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022. Abdominal Obesity, Inflammation, and Colorectal Cancer Risk. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.983160/full

- Park JW et al. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021. Visceral Fat and Colorectal Cancer Outcomes. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8761926/

- Lengyel E et al. Steroids. 2022. Cancer’s Fuel from Fat: Fatty-Acid Oxidation in Tumor Growth. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044579X22001766

- Chen J et al. Int J Oncol. 2023. Obesity, Gut Microbiome, and Gastrointestinal Cancers.

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/ijo/64/1/4# - Harvard Health Publishing. Body fat may predict aggressive prostate cancer.

https://www.health.harvard.edu/mens-health/body-fat-may-predict-aggressive-prostate-cancer - Lavalette C, et al. Abdominal obesity and prostate cancer risk. PubMed Central (review).

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6195387/ - SolutionHealth. 6 hidden dangers of belly fat in men (heart disease, stroke, diabetes explained).

https://www.solutionhealth.org/2024/07/25/6-hidden-dangers-of-belly-fat-in-men/ - Ahmed KY, Aychiluhm SB, Thapa S, et al. Cardiometabolic Outcomes Among Adults With Abdominal Obesity and Normal Body Mass Index. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2537942. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.37942

- Henderson, J. (2025, December 3). Belly Fat May Be Stronger Predictor of Heart Damage Than BMI. Medpagetoday.com; MedpageToday. https://www.medpagetoday.com/meetingcoverage/rsna/118818

- Epel ES, Hartman A, Jacobs LM, Leung C, Cohn MA, Jensen L, et al. Association of a Workplace Sales Ban on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages With Employee Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Health. JAMA Network Open. 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4434

- JAMA Network Open. 2023. Dose–Response of Aerobic Exercise and Visceral Fat.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2828487 - Harvard Health Publishing. Taking Aim at Belly Fat. Exercise and Lifestyle Guidance.

https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/taking-aim-at-belly-fat - Martínez-González MA et al. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2023. Mediterranean Diet and Visceral Fat Loss.

https://nutritionandmetabolism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12986-023-00706-4 - Sun Y et al. Frontiers in Physiology. 2022. Effects of Different Exercise Types on Visceral Fat in Young Adults. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10456392/

- Harvard Health Publishing. Taking Aim at Belly Fat. 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/taking-aim-at-belly-fat

- University of Sydney. 2021. Belly Fat Resistant to Every-Other-Day Fasting Study. https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2021/03/03/belly-fat-resistant-to-every-other-day-fasting-study.html

- Sato Y et al. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021. Possible Mechanisms to Explain Abdominal Fat Loss Effect of Exercise Training.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.789463/full